Part of Putting the “You” in CPU: a rabbit hole into how your computer runs programs.

Chapter 4:

Becoming an Elf-Lord

Edit on GitHub

We pretty thoroughly understand execve now. At the end of most paths, the kernel will reach a final program containing machine code for it to launch. Typically, a setup process is required before actually jumping to the code — for example, different parts of the program have to be loaded into the right places in memory. Each program needs different amounts of memory for different things, so we have standard file formats that specify how to set up a program for execution. While Linux supports many such formats, the most common format by far is ELF (executable and linkable format).

(Thank you to Nicky Case for the adorable drawing.)

Aside: are elves everywhere?

When you run an app or command-line program on Linux, it’s exceedingly likely that it’s an ELF binary. However, on macOS the de-facto format is Mach-O instead. Mach-O does all the same things as ELF but is structured differently. On Windows, .exe files use the Portable Executable format which is, again, a different format with the same concept.

In the Linux kernel, ELF binaries are handled by the binfmt_elf handler, which is more complex than many other handlers and contains thousands of lines of code. It’s responsible for parsing out certain details from the ELF file and using them to load the process into memory and execute it.

I ran some command-line kung fu to sort binfmt handlers by line count:

$ wc -l binfmt_* | sort -nr | sed 1d

2181 binfmt_elf.c

1658 binfmt_elf_fdpic.c

944 binfmt_flat.c

836 binfmt_misc.c

158 binfmt_script.c

64 binfmt_elf_test.cFile Structure

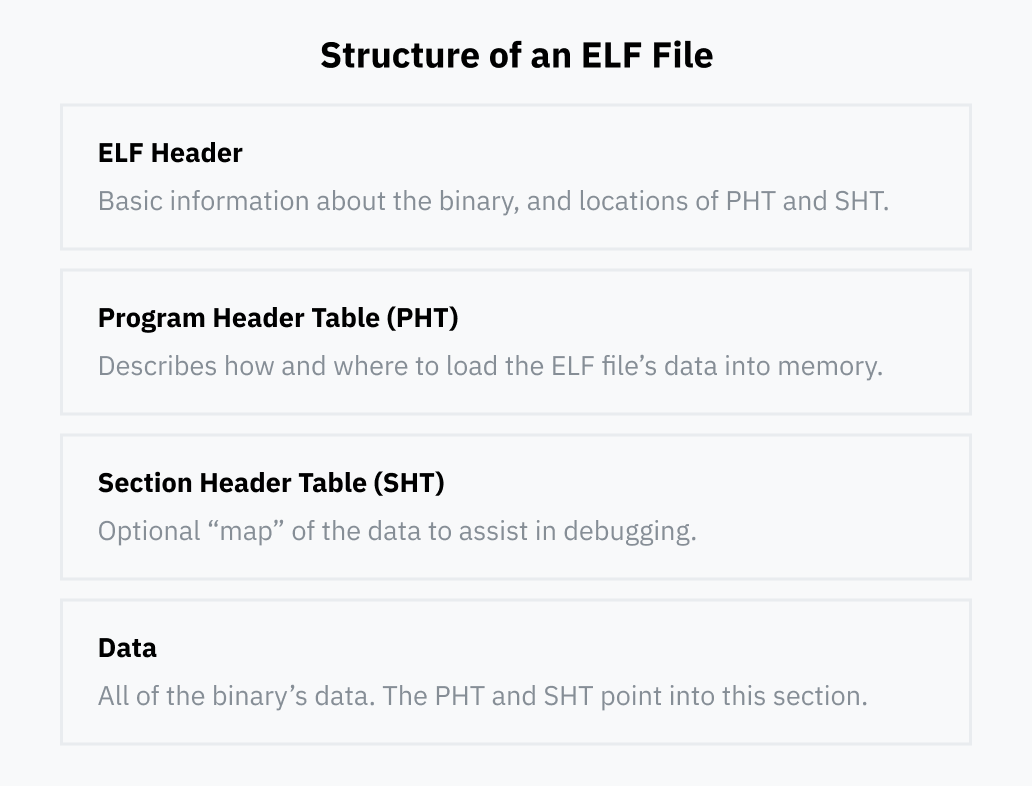

Before looking more deeply at how binfmt_elf executes ELF files, let’s take a look at the file format itself. ELF files are typically made up of four parts:

ELF Header

Every ELF file has an ELF header. It has the very important job of conveying basic information about the binary such as:

- What processor it’s designed to run on. ELF files can contain machine code for different processor types, like ARM and x86.

- Whether the binary is meant to be run on its own as an executable, or whether it’s meant to be loaded by other programs as a “dynamically linked library.” We’ll go into details about what dynamic linking is soon.

- The entry point of the executable. Later sections specify exactly where to load data contained in the ELF file into memory. The entry point is a memory address pointing to where the first machine code instruction is in memory after the entire process has been loaded.

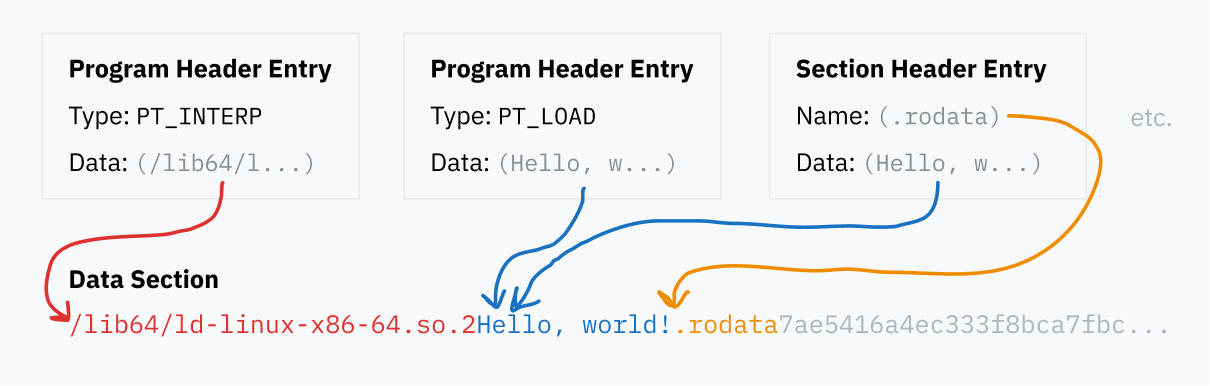

The ELF header is always at the start of the file. It specifies the locations of the program header table and section header, which can be anywhere within the file. Those tables, in turn, point to data stored elsewhere in the file.

Program Header Table

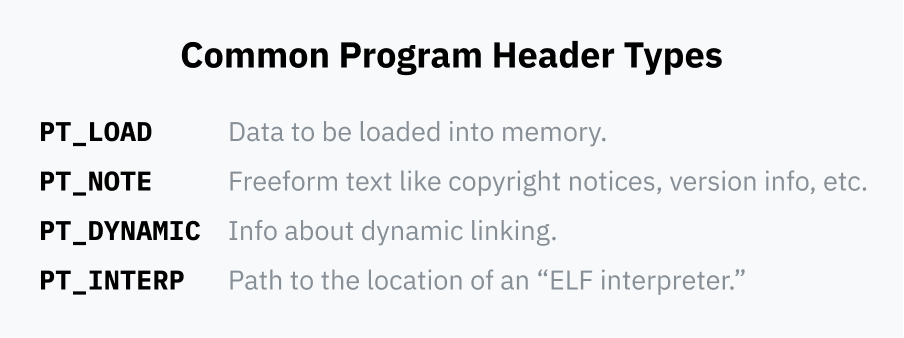

The program header table is a series of entries containing specific details for how to load and execute the binary at runtime. Each entry has a type field that says what detail it’s specifying — for example, PT_LOAD means it contains data that should be loaded into memory, but PT_NOTE means the segment contains informational text that shouldn’t necessarily be loaded anywhere.

Each entry specifies information about where its data is in the file and, sometimes, how to load the data into memory:

- It points to the position of its data within the ELF file.

- It can specify what virtual memory address the data should be loaded into memory at. This is typically left blank if the segment isn’t meant to be loaded into memory.

- Two fields specify the length of the data: one for the length of the data in the file, and one for the length of the memory region to be created. If the memory region length is longer than the length in the file, the extra memory will be filled with zeroes. This is beneficial for programs that might want a static segment of memory to use at runtime; these empty segments of memory are typically called BSS segments.

- Finally, a flags field specifies what operations should be permitted if it’s loaded into memory:

PF_Rmakes it readable,PF_Wmakes it writable, andPF_Xmeans it’s code that should be allowed to execute on the CPU.

Section Header Table

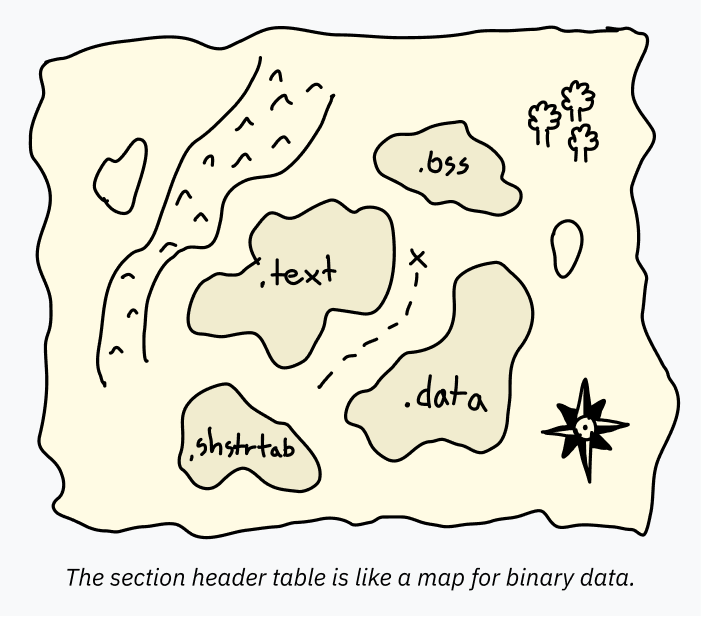

The section header table is a series of entries containing information about sections. This section information is like a map, charting the data inside the ELF file. It makes it easy for programs like debuggers to understand the intended uses of different portions of the data.

For example, the program header table can specify a large swath of data to be loaded into memory together. That single PT_LOAD block might contain both code and global variables! There’s no reason those have to be specified separately to run the program; the CPU just starts at the entry point and steps forward, accessing data when and where the program requests it. However, software like a debugger for analyzing the program needs to know exactly where each area starts and ends, otherwise it might try to decode some text that says “hello” as code (and since that isn’t valid code, explode). This information is stored in the section header table.

While it’s usually included, the section header table is actually optional. ELF files can run perfectly well with the section header table completely removed, and developers who want to hide what their code does will sometimes intentionally strip or mangle the section header table from their ELF binaries to make them harder to decode.

Each section has a name, a type, and some flags that specify how it’s intended to be used and decoded. Standard names usually start with a dot by convention. The most common sections are:

.text: machine code to be loaded into memory and executed on the CPU.SHT_PROGBITStype with theSHF_EXECINSTRflag to mark it as executable, and theSHF_ALLOCflag which means it’s loaded into memory for execution. (Don’t get confused by the name, it’s still just binary machine code! I always found it somewhat strange that it’s called.textdespite not being readable “text.“).data: initialized data hardcoded in the executable to be loaded into memory. For example, a global variable containing some text might be in this section. If you write low-level code, this is the section where statics go. This also has the typeSHT_PROGBITS, which just means the section contains “information for the program.” Its flags areSHF_ALLOCandSHF_WRITEto mark it as writable memory..bss: I mentioned earlier that it’s common to have some allocated memory that starts out zeroed. It would be a waste to include a bunch of empty bytes in the ELF file, so a special segment type called BSS is used. It’s helpful to know about BSS segments during debugging, so there’s also a section header table entry that specifies the length of the memory to be allocated. It’s of typeSHT_NOBITS, and is flaggedSHF_ALLOCandSHF_WRITE..rodata: this is like.dataexcept it’s read-only. In a very basic C program that runsprintf("Hello, world!"), the string “Hello world!” would be in a.rodatasection, while the actual printing code would be in a.textsection..shstrtab: this is a fun implementation detail! The names of sections themselves (like.textand.shstrtab) aren’t included directly in the section header table. Instead, each entry contains an offset to a location in the ELF file that contains its name. This way, each entry in the section header table can be the same size, making them easier to parse — an offset to the name is a fixed-size number, whereas including the name in the table would use a variable-size string. All of this name data is stored in its own section called.shstrtab, of typeSHT_STRTAB.

Data

The program and section header table entries all point to blocks of data within the ELF file, whether to load them into memory, to specify where program code is, or just to name sections. All of these different pieces of data are contained in the data section of the ELF file.

A Brief Explanation of Linking

Back to the binfmt_elf code: the kernel cares about two types of entries in the program header table.

PT_LOAD segments specify where all the program data, like the .text and .data sections, need to be loaded into memory. The kernel reads these entries from the ELF file to load the data into memory so the program can be executed by the CPU.

The other type of program header table entry that the kernel cares about is PT_INTERP, which specifies a “dynamic linking runtime.”

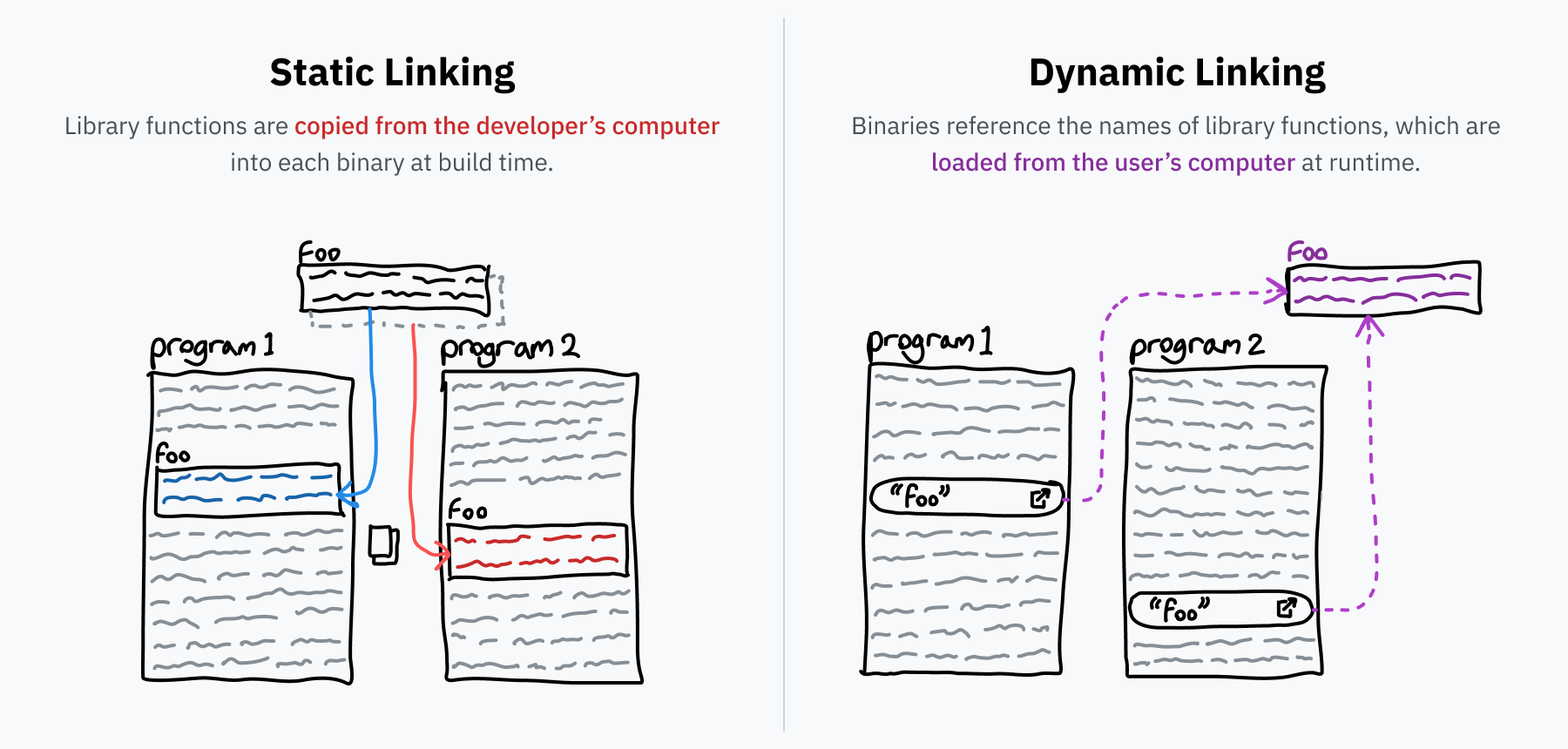

Before we talk about what dynamic linking is, let’s talk about “linking” in general. Programmers tend to build their programs on top of libraries of reusable code — for example, libc, which we talked about earlier. When turning your source code into an executable binary, a program called a linker resolves all these references by finding the library code and copying it into the binary. This process is called static linking, which means external code is included directly in the file that’s distributed.

However, some libraries are super common. You’ll find libc is used by basically every program under the sun, since it’s the canonical interface for interacting with the OS through syscalls. It would be a terrible use of space to include a separate copy of libc in every single program on your computer. Also, it might be nice if bugs in libraries could be fixed in one place rather than having to wait for each program that uses the library to be updated. Dynamic linking is the solution to these problems.

If a statically linked program needs a function foo from a library called bar, the program would include a copy of the entirety of foo. However, if it’s dynamically linked it would only include a reference saying “I need foo from library bar.” When the program is run, bar is hopefully installed on the computer and the foo function’s machine code can be loaded into memory on-demand. If the computer’s installation of the bar library is updated, the new code will be loaded the next time the program runs without needing any change in the program itself.

Dynamic Linking in the Wild

On Linux, dynamically linkable libraries like bar are typically packaged into files with the .so (Shared Object) extension. These .so files are ELF files just like programs — you may recall that the ELF header includes a field to specify whether the file is an executable or a library. In addition, shared objects have a .dynsym section in the section header table which contains information on what symbols are exported from the file and can be dynamically linked to.

On Windows, libraries like bar are packaged into .dll (dynamic link library) files. macOS uses the .dylib (dynamically linked library) extension. Just like macOS apps and Windows .exe files, these are formatted slightly differently from ELF files but are the same concept and technique.

An interesting distinction between the two types of linking is that with static linking, only the portions of the library that are used are included in the executable and thus loaded into memory. With dynamic linking, the entire library is loaded into memory. This might initially sound less efficient, but it actually allows modern operating systems to save more space by loading a library into memory once and then sharing that code between processes. Only code can be shared as the library needs different state for different programs, but the savings can still be on the order of tens to hundreds of megabytes of RAM.

Execution

Let’s hop on back to the kernel running ELF files: if the binary it’s executing is dynamically linked, the OS can’t just jump to the binary’s code right away because there would be missing code — remember, dynamically linked programs only have references to the library functions they need!

To run the binary, the OS needs to figure out what libraries are needed, load them, replace all the named pointers with actual jump instructions, and then start the actual program code. This is very complex code that interacts deeply with the ELF format, so it’s usually a standalone program rather than part of the kernel. ELF files specify the path to the program they want to use (typically something like /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2) in a PT_INTERP entry in the program header table.

After reading the ELF header and scanning through the program header table, the kernel can set up the memory structure for the new program. It starts by loading all PT_LOAD segments into memory, populating the program’s static data, BSS space, and machine code. If the program is dynamically linked, the kernel will have to execute the ELF interpreter (PT_INTERP), so it also loads the interpreter’s data, BSS, and code into memory.

Now the kernel needs to set the instruction pointer for the CPU to restore when returning to userland. If the executable is dynamically linked, the kernel sets the instruction pointer to the start of the ELF interpreter’s code in memory. Otherwise, the kernel sets it to the start of the executable.

The kernel is almost ready to return from the syscall (remember, we’re still in execve). It pushes the argc, argv, and environment variables to the stack for the program to read when it begins.

The registers are now cleared. Before handling a syscall, the kernel stores the current value of registers to the stack to be restored when switching back to user space. Before returning to user space, the kernel zeroes this part of the stack.

Finally, the syscall is over and the kernel returns to userland. It restores the registers, which are now zeroed, and jumps to the stored instruction pointer. That instruction pointer is now the starting point of the new program (or the ELF interpreter) and the current process has been replaced!

Continue to Chapter 5: The Translator in Your Computer