Part of Putting the “You” in CPU: a rabbit hole into how your computer runs programs.

Chapter 5:

The Translator in Your Computer

Edit on GitHub

Up until now, every time I’ve talked about reading and writing memory was a little wishy-washy. For example, ELF files specify specific memory addresses to load data into, so why aren’t there problems with different processes trying to use conflicting memory? Why does each process seem to have a different memory environment?

Also, how exactly did we get here? We understand that execve is a syscall that replaces the current process with a new program, but this doesn’t explain how multiple processes can be started. It definitely doesn’t explain how the very first program runs — what chicken (process) lays (spawns) all the other eggs (other processes)?

We’re nearing the end of our journey. After these two questions are answered, we’ll have a mostly complete understanding of how your computer got from bootup to running the software you’re using right now.

Memory is Fake

So… about memory. It turns out that when the CPU reads from or writes to a memory address, it’s not actually referring to that location in physical memory (RAM). Rather, it’s pointing to a location in virtual memory space.

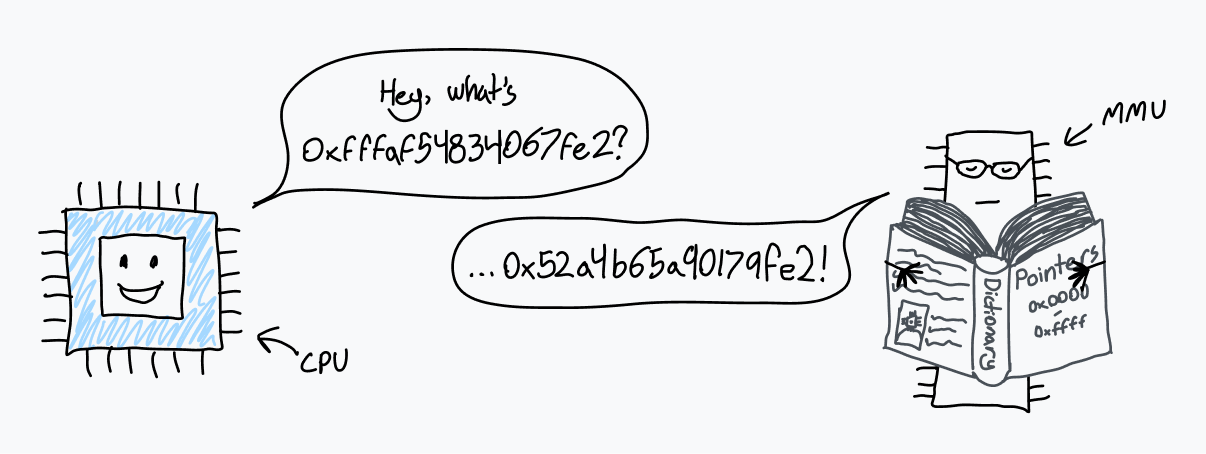

The CPU talks to a chip called a memory management unit (MMU). The MMU works like a translator with a dictionary that translates locations in virtual memory to locations in RAM. When the CPU is given an instruction to read from memory address 0xfffaf54834067fe2, it asks the MMU to translate that address. The MMU looks it up in the dictionary, discovers that the matching physical address is 0x53a4b64a90179fe2, and sends the number back to the CPU. The CPU can then read from that address in RAM.

When the computer first boots up, memory accesses go directly to physical RAM. Immediately after startup, the OS creates the translation dictionary and tells the CPU to start using the MMU.

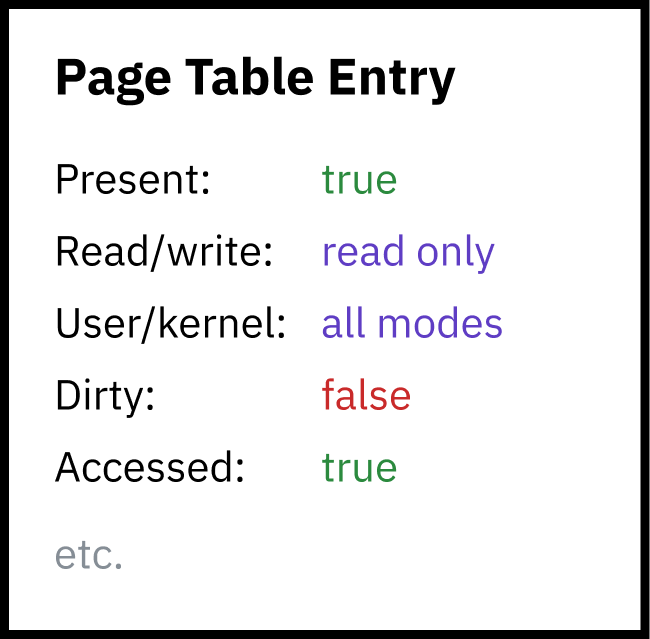

This dictionary is actually called a page table, and this system of translating every memory access is called paging. Entries in the page table are called pages and each one represents how a certain chunk of virtual memory maps to RAM. These chunks are always a fixed size, and each processor architecture has a different page size. x86-64 has a default 4 KiB page size, meaning each page specifies the mapping for a block of memory 4,096 bytes long.

In other words, with 4 KiB pages the bottom 12 bits of an address will always be the same before and after MMU translation — 12, because that’s the amount of bits needed to index the 4,096-byte page you get post-translation.

x86-64 also allows operating systems to enable larger 2 MiB or 4 GiB pages, which can improve address translation speed but increase memory fragmentation and waste. The larger the page size, the smaller the portion of the address that’s translated by the MMU.

The page table itself just resides in RAM. While it can contain millions of entries, each entry’s size is only on the order of a couple bytes, so the page table doesn’t take up too much space.

To enable paging at boot, the kernel first constructs the page table in RAM. Then, it stores the physical address of the start of the page table in a register called the page table base register (PTBR). Finally, the kernel enables paging to translate all memory accesses with the MMU. On x86-64, the top 20 bits of control register 3 (CR3) function as the PTBR. Bit 31 of CR0, designated PG for Paging, is set to 1 to enable paging.

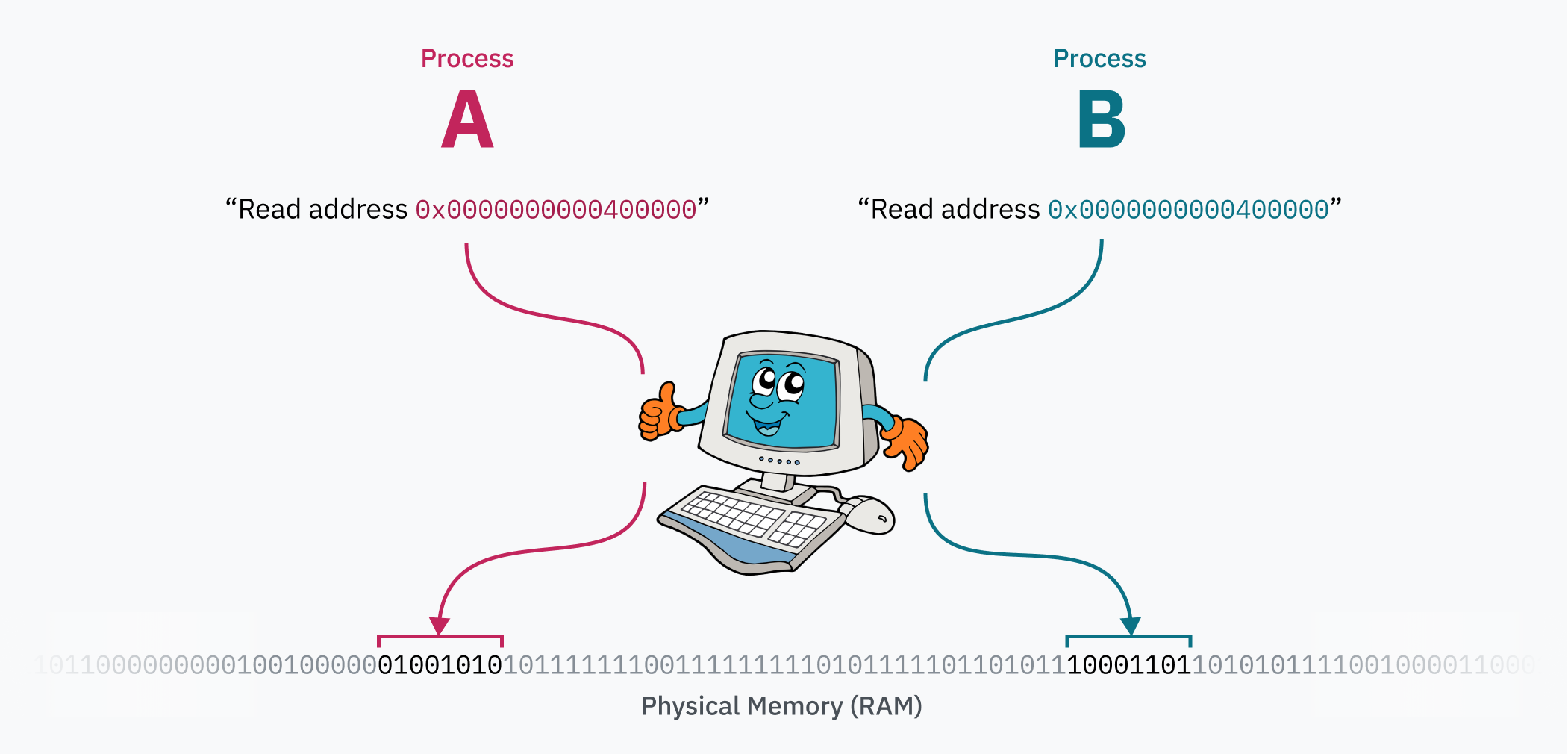

The magic of the paging system is that the page table can be edited while the computer is running. This is how each process can have its own isolated memory space — when the OS switches context from one process to another, an important task is remapping the virtual memory space to a different area in physical memory. Let’s say you have two processes: process A can have its code and data (likely loaded from an ELF file!) at 0x0000000000400000, and process B can access its code and data from the very same address. Those two processes can even be instances of the same program, because they aren’t actually fighting over that address range! The data for process A is somewhere far from process B in physical memory, and is mapped to 0x0000000000400000 by the kernel when switching to the process.

Aside: cursed ELF fact

In certain situations,

binfmt_elfhas to map the first page of memory to zeroes. Some programs written for UNIX System V Release 4.0 (SVr4), an OS from 1988 that was the first to support ELF, rely on null pointers being readable. And somehow, some programs still rely on that behavior.It seems like the Linux kernel dev implementing this was a little disgruntled:

“Why this, you ask??? Well SVr4 maps page 0 as read-only, and some applications ‘depend’ upon this behavior. Since we do not have the power to recompile these, we emulate the SVr4 behavior. Sigh.”

Sigh.

Security with Paging

The process isolation enabled by memory paging improves code ergonomics (processes don’t need to be aware of other processes to use memory), but it also creates a level of security: processes cannot access memory from other processes. This half answers one of the original questions from the start of this article:

If programs run directly on the CPU, and the CPU can directly access RAM, why can’t code access memory from other processes, or, god forbid, the kernel?

Remember that? It feels like so long ago…

What about that kernel memory, though? First things first: the kernel obviously needs to store plenty of data of its own to keep track of all the processes running and even the page table itself. Every time a hardware interrupt, software interrupt, or system call is triggered and the CPU enters kernel mode, the kernel code needs to access that memory somehow.

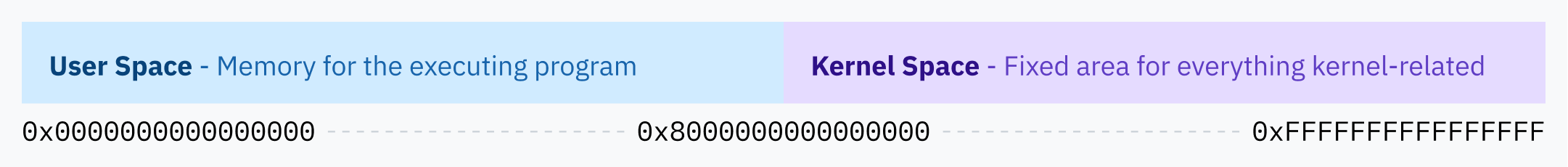

Linux’s solution is to always allocate the top half of the virtual memory space to the kernel, so Linux is called a higher half kernel. Windows employs a similar technique, while macOS is… slightly more complicated and caused my brain to ooze out of my ears reading about it. ~(++)~

It would be terrible for security if userland processes could read or write kernel memory though, so paging enables a second layer of security: each page must specify permission flags. One flag determines whether the region is writable or only readable. Another flag tells the CPU that only kernel mode is allowed to access the region’s memory. This latter flag is used to protect the entire higher half kernel space — the entire kernel memory space is actually available in the virtual memory mapping for user space programs, they just don’t have the permissions to access it.

The page table itself is actually contained within the kernel memory space! When the timer chip triggers a hardware interrupt for process switching, the CPU switches the privilege level to kernel mode and jumps to Linux kernel code. Being in kernel mode (Intel ring 0) allows the CPU to access the kernel-protected memory region. The kernel can then write to the page table (residing somewhere in that upper half of memory) to remap the lower half of virtual memory for the new process. When the kernel switches to the new process and the CPU enters user mode, it can no longer access any of the kernel memory.

Just about every memory access goes through the MMU. Interrupt descriptor table handler pointers? Those address the kernel’s virtual memory space as well.

Hierarchical Paging and Other Optimizations

64-bit systems have memory addresses that are 64 bits long, meaning the 64-bit virtual memory space is a whopping 16 exbibytes in size. That is incredibly large, far larger than any computer that exists today or will exist any time soon. As far as I can tell, the most RAM in any computer ever was in the Blue Waters supercomputer, with over 1.5 petabytes of RAM. That’s still less than 0.01% of 16 EiB.

If an entry in the page table was required for every 4 KiB section of virtual memory space, you would need 4,503,599,627,370,496 page table entries. With 8-byte-long page table entries, you would need 32 pebibytes of RAM just to store the page table alone. You may notice that’s still larger than the world record for the most RAM in a computer.

Aside: why the weird units?

I know it’s uncommon and really ugly, but I find it important to clearly differentiate between binary byte size units (powers of 2) and metric ones (powers of 10). A kilobyte, kB, is an SI unit that means 1,000 bytes. A kibibyte, KiB, is an IEC-recommended unit that means 1,024 bytes. In terms of CPUs and memory addresses, byte counts are usually powers of two because computers are binary systems. Using KB (or worse, kB) to mean 1,024 would be more ambiguous.

Since it would be impossible (or at least incredibly impractical) to have sequential page table entries for the entire possible virtual memory space, CPU architectures implement hierarchical paging. In hierarchical paging systems, there are multiple levels of page tables of increasingly small granularity. The top level entries cover large blocks of memory and point to page tables of smaller blocks, creating a tree structure. The individual entries for blocks of 4 KiB or whatever the page size is are the leaves of the tree.

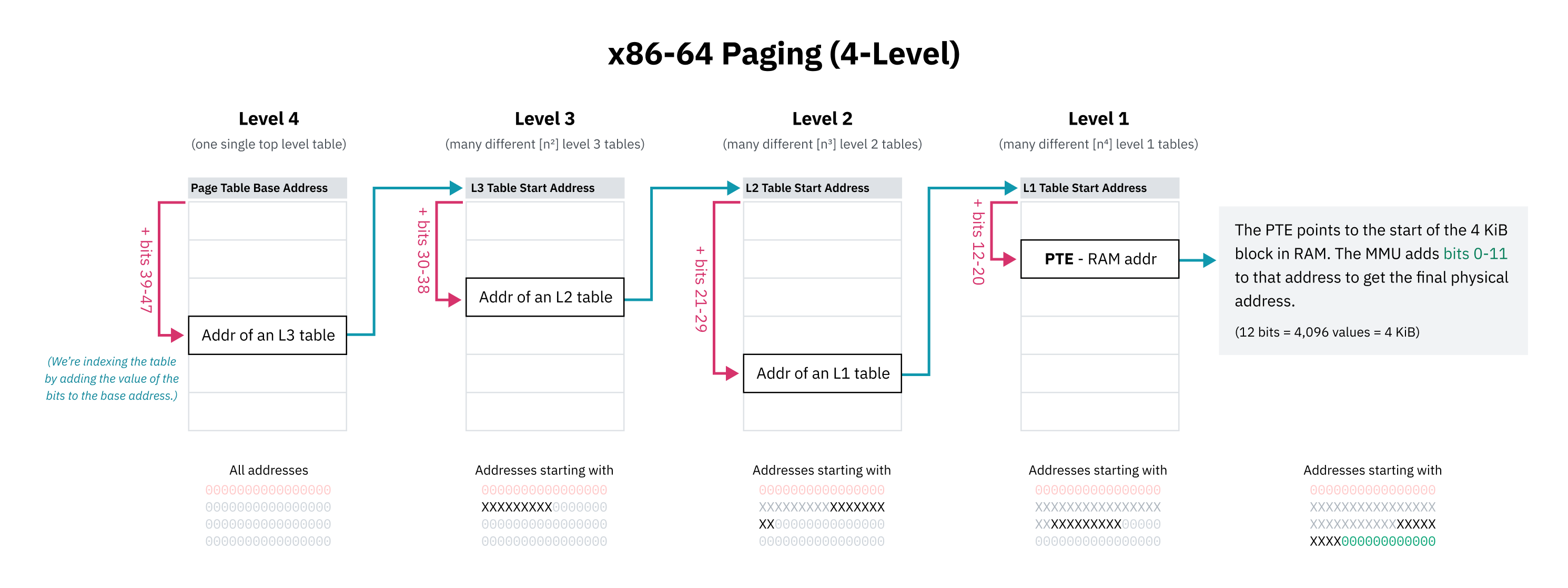

x86-64 historically uses 4-level hierarchical paging. In this system, each page table entry is found by offsetting the start of the containing table by a portion of the address. This portion starts with the most significant bits, which work as a prefix so the entry covers all addresses starting with those bits. The entry points to the start of the next level of table containing the subtrees for that block of memory, which are again indexed with the next collection of bits.

The designers of x86-64’s 4-level paging also chose to ignore the top 16 bits of all virtual pointers to save page table space. 48 bits gets you a 128 TiB virtual address space, which was deemed to be large enough. (The full 64 bits would get you 16 EiB, which is kind of a lot.)

Since the first 16 bits are skipped, the “most significant bits” for indexing the first level of the page table actually start at bit 47 rather than 63. This also means the higher half kernel diagram from earlier in this chapter was technically inaccurate; the kernel space start address should’ve been depicted as the midpoint of an address space smaller than 64 bits.

Hierarchical paging solves the space problem because at any level of the tree, the pointer to the next entry can be null (0x0). This allows entire subtrees of the page table to be elided, meaning unmapped areas of the virtual memory space don’t take up any space in RAM. Lookups at unmapped memory addresses can fail quickly because the CPU can error as soon as it sees an empty entry higher up in the tree. Page table entries also have a presence flag that can be used to mark them as unusable even if the address appears valid.

Another benefit of hierarchical paging is the ability to efficiently switch out large sections of the virtual memory space. A large swath of virtual memory might be mapped to one area of physical memory for one process, and a different area for another process. The kernel can store both mappings in memory and simply update the pointers at the top level of the tree when switching processes. If the entire memory space mapping was stored as a flat array of entries, the kernel would have to update a lot of entries, which would be slow and still require independently keeping track of the memory mappings for each process.

I said x86-64 “historically” uses 4-level paging because recent processors implement 5-level paging. 5-level paging adds another level of indirection as well as 9 more addressing bits to expand the address space to 128 PiB with 57-bit addresses. 5-level paging is supported by operating systems including Linux since 2017 as well as recent Windows 10 and 11 server versions.

Aside: physical address space limits

Just as operating systems don’t use all 64 bits for virtual addresses, processors don’t use entire 64-bit physical addresses. When 4-level paging was the standard, x86-64 CPUs didn’t use more than 46 bits, meaning the physical address space was limited to only 64 TiB. With 5-level paging, support has been extended to 52 bits, supporting a 4 PiB physical address space.

On the OS level, it’s advantageous for the virtual address space to be larger than the physical address space. As Linus Torvalds said, “[i]t needs to be bigger, by a factor of at least two, and that’s quite frankly pushing it, and you’re much better off having a factor of ten or more. Anybody who doesn’t get that is a moron. End of discussion.”

Swapping and Demand Paging

A memory access might fail for a couple reasons: the address might be out of range, it might not be mapped by the page table, or it might have an entry that’s marked as not present. In any of these cases, the MMU will trigger a hardware interrupt called a page fault to let the kernel handle the problem.

In some cases, the read was truly invalid or prohibited. In these cases, the kernel will probably terminate the program with a segmentation fault error.

$ ./program

Segmentation fault (core dumped)

$Aside: segfault ontology

“Segmentation fault” means different things in different contexts. The MMU triggers a hardware interrupt called a “segmentation fault” when memory is read without permission, but “segmentation fault” is also the name of a signal the OS can send to running programs to terminate them due to any illegal memory access.

In other cases, memory accesses can intentionally fail, allowing the OS to populate the memory and then hand control back to the CPU to try again. For example, the OS can map a file on disk to virtual memory without actually loading it into RAM, and then load it into physical memory when the address is requested and a page fault occurs. This is called demand paging.

For one, this allows syscalls like mmap that lazily map entire files from disk to virtual memory to exist. If you’re familiar with LLaMa.cpp, a runtime for a leaked Facebook language model, Justine Tunney recently significantly optimized it by making all the loading logic use mmap. (If you haven’t heard of her before, check her stuff out! Cosmopolitan Libc and APE are really cool and might be interesting if you’ve been enjoying this article.)

Apparently there’s a lot of drama about Justine’s involvement in this change. Just pointing this out so I don’t get screamed at by random internet users. I must confess that I haven’t read most of the drama, and everything I said about Justine’s stuff being cool is still very true.

When you execute a program and its libraries, the kernel doesn’t actually load anything into memory. It only creates an mmap of the file — when the CPU tries to execute the code, the page immediately faults and the kernel replaces the page with a real block of memory.

Demand paging also enables the technique that you’ve probably seen under the name “swapping” or “paging.” Operating systems can free up physical memory by writing memory pages to disk and then removing them from physical memory but keeping them in virtual memory with the present flag set to 0. If that virtual memory is read, the OS can then restore the memory from disk to RAM and set the present flag back to 1. The OS may have to swap a different section of RAM to make space for the memory being loaded from disk. Disk reads and writes are slow, so operating systems try to make swapping happen as little as possible with efficient page replacement algorithms.

An interesting hack is to use page table physical memory pointers to store the locations of files within physical storage. Since the MMU will page fault as soon as it sees a negative present flag, it doesn’t matter that they are invalid memory addresses. This isn’t practical in all cases, but it’s amusing to think about.

Continue to Chapter 6: Let's Talk About Forks and Cows